This week we're taking it back to our first big push in 2013 to keep the garden growing. Check out some great excerpts from a long article about the history of Brewerytown Garden (formerly Marathon Farm):

Originally published in Hidden City Philadelphia, December 16, 2013

In Brewerytown, Pushing To Revive Marathon Farm

by Cary Betagole

Of all the Philadelphia restaurants that have joined the burgeoning farm-to-table movement, Marathon Grill was perhaps the most unlikely. The local chain of high-volume, casual eateries is better known for serving turkey club sandwiches and cobb salads than for the provenance of its vegetables.

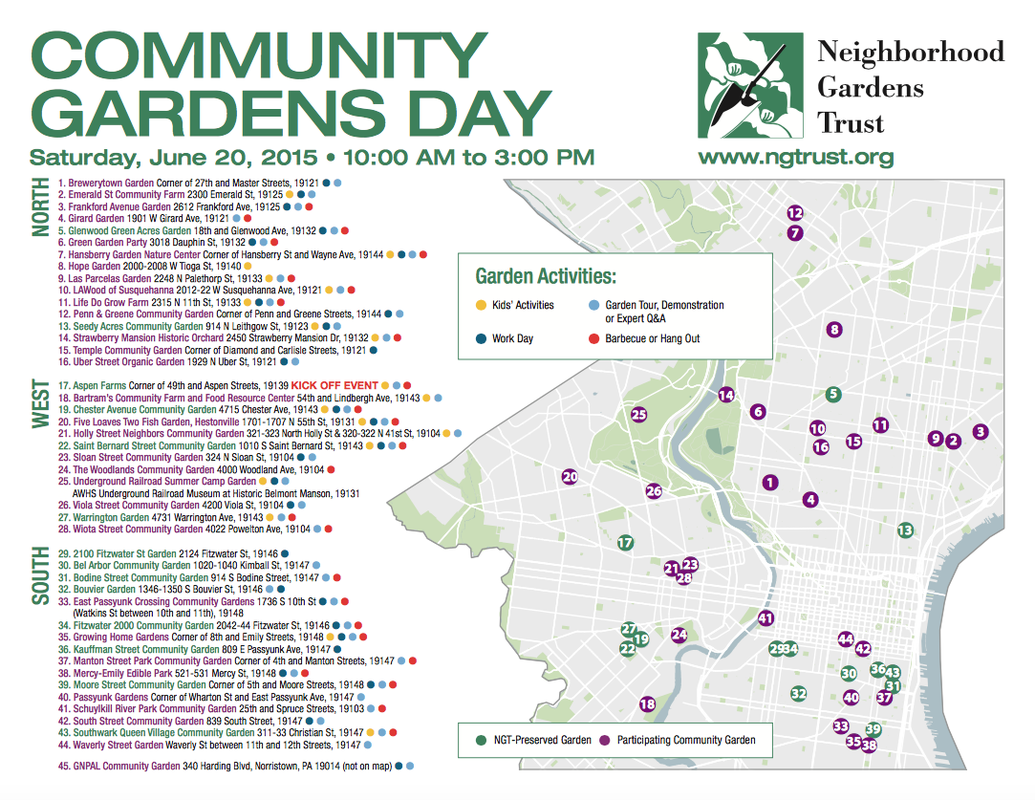

But on an overcast Monday in late March, 2011, Marathon Restaurants president Cary Borish was in Brewerytown for the launch of Marathon Farm. The ambitious plan called for selling half the farm’s produce at market value to Marathon Restaurants, and selling the other half at affordable prices to neighborhood residents via farm stands. A section of the farm would be set aside for community gardeners, and Borish pledged to invest $100,000 in infrastructure, community programing, supplies and a farm manager.

The project had the support of city officials, including Mayor Michael Nutter, who spoke at the ribbon cutting for the 15,750 square foot lot on the corner of 27th and Master. The City, which has owned the triangle-shaped parcel since the 19th century, leased the land to Marathon Loves Philly, a non-profit created by the politically connected Borish. The price was a dollar a year, according to several sources. After the three year term was up, a longer lease would be discussed if everything went well.

Marathon Farm got off to a strong start. Borish hired Patrick Dunn, a founder of Emerald Farm in Kensington, to help get the farm up and running, along with a full-time farm manager, Adam Hill. Much of the infrastructure was built in the spring, and by mid-summer there was a bumper crop of tomatoes on the vines. Almost three years later, three of Marathon’s six restaurants have closed, and one of the remaining locations is operating under Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection. Marathon Farm has also fared poorly, as support from the company dwindled, and nearly stopped altogether this summer. The situation began to go downhill in May 2012, when Hill took a job with the Pennsylvania Horticultural Society and Borish did not hire a replacement. Instead, he paid Eddie Branch, an enthusiastic volunteer who learned the basics of planting and harvesting vegetables under Hill’s tutelage, a stipend to take care of the entire farm.

Branch, who has lived on 27th Street for 49 years, also ran a school lunch program in the farm’s second summer, but ended it after several weeks when it proved to be more work than he could handle alone. Despite his lack of experience, Branch was able to keep an on-site farm stand running with moderate success through the summers of 2011 and 2012. “I love everything about this farm,” said Branch, who makes sure to attach this caveat to any frustrated statement he makes about the current condition of the farm.

Today, the garden’s raised beds lie fallow. Yet much potentially useful infrastructure installed by Borish remains in place, including a greenhouse, shed and irrigation system. A beehive murmurs next to the west entrance, and a mural of radishes and sunflowers painted by Mural Arts adorns the back wall.

The small group of urban gardeners who have tended community plots at the site would like to build on this foundation, even though the project didn’t work as planned. But with Marathon’s lease with the Department of Public Property set to expire in April, the big question is whether they will get the chance to do so.

Originally published in Hidden City Philadelphia, December 16, 2013

In Brewerytown, Pushing To Revive Marathon Farm

by Cary Betagole

Of all the Philadelphia restaurants that have joined the burgeoning farm-to-table movement, Marathon Grill was perhaps the most unlikely. The local chain of high-volume, casual eateries is better known for serving turkey club sandwiches and cobb salads than for the provenance of its vegetables.

But on an overcast Monday in late March, 2011, Marathon Restaurants president Cary Borish was in Brewerytown for the launch of Marathon Farm. The ambitious plan called for selling half the farm’s produce at market value to Marathon Restaurants, and selling the other half at affordable prices to neighborhood residents via farm stands. A section of the farm would be set aside for community gardeners, and Borish pledged to invest $100,000 in infrastructure, community programing, supplies and a farm manager.

The project had the support of city officials, including Mayor Michael Nutter, who spoke at the ribbon cutting for the 15,750 square foot lot on the corner of 27th and Master. The City, which has owned the triangle-shaped parcel since the 19th century, leased the land to Marathon Loves Philly, a non-profit created by the politically connected Borish. The price was a dollar a year, according to several sources. After the three year term was up, a longer lease would be discussed if everything went well.

Marathon Farm got off to a strong start. Borish hired Patrick Dunn, a founder of Emerald Farm in Kensington, to help get the farm up and running, along with a full-time farm manager, Adam Hill. Much of the infrastructure was built in the spring, and by mid-summer there was a bumper crop of tomatoes on the vines. Almost three years later, three of Marathon’s six restaurants have closed, and one of the remaining locations is operating under Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection. Marathon Farm has also fared poorly, as support from the company dwindled, and nearly stopped altogether this summer. The situation began to go downhill in May 2012, when Hill took a job with the Pennsylvania Horticultural Society and Borish did not hire a replacement. Instead, he paid Eddie Branch, an enthusiastic volunteer who learned the basics of planting and harvesting vegetables under Hill’s tutelage, a stipend to take care of the entire farm.

Branch, who has lived on 27th Street for 49 years, also ran a school lunch program in the farm’s second summer, but ended it after several weeks when it proved to be more work than he could handle alone. Despite his lack of experience, Branch was able to keep an on-site farm stand running with moderate success through the summers of 2011 and 2012. “I love everything about this farm,” said Branch, who makes sure to attach this caveat to any frustrated statement he makes about the current condition of the farm.

Today, the garden’s raised beds lie fallow. Yet much potentially useful infrastructure installed by Borish remains in place, including a greenhouse, shed and irrigation system. A beehive murmurs next to the west entrance, and a mural of radishes and sunflowers painted by Mural Arts adorns the back wall.

The small group of urban gardeners who have tended community plots at the site would like to build on this foundation, even though the project didn’t work as planned. But with Marathon’s lease with the Department of Public Property set to expire in April, the big question is whether they will get the chance to do so.

Sam Gainsburg (r) and neighborhood resident Sudha Suryadevara (l)

Photo: Cary Betogle

Photo: Cary Betogle

A community-based future for the farm?

Sam Gainsburg, a Fairmount resident who gardens a plot at Marathon Farm, hopes to revive the farm under community control. She’s led discussions with Borish and the Greater Brewerytown CDC (GBCDC) and WGCC, and also organized a garden cleanup on November 16 that included the two groups. “My goal is for this committee to make democratic decisions and apply for different grants and programs together.” Gainsburg said. “I really want to hear from the community and find out what they need from the space.”

The people invested in the future of the farm say they will prioritize community ownership and shared responsibility for the space, a pivot from a failed model that depended heavily on a single organization, Marathon. “We need manpower, knocking on doors, cleaning, rebuilding the raised beds,” said Gainsburg, who would also like to help reinvigorate the farm stand and create a new partnership with WGCC.

Striking this balance will only become more vital as Brewerytown continues to slowly gentrify. “We’re working on a structure that’s inclusive of the native population and newcomers to the neighborhood,” said Charles Holliday of GBCDC. “Right now the system we have in place resembles squatting. It’s going to take time. It’s only been two years. I don’t know that the community was ready.” Branch laments that African - American residents living adjacent to the farm have not become more involved, but he agrees it will take time and a consistent presence.

Borish has become involved with the project again in recent weeks, but won’t necessarily have a future role with the farm. “I feel sad about the condition of the farm,” said Borish. “It’s clear that I haven’t done a great job. Have I lost some passion for the project? Yes.” He added: “I’m willing to have any or no involvement. Whatever is in the best interest of the folks taking over the farm.”

Meanwhile, Gainsburg is thinking through the logistics of how to create a shared sense of ownership and collaboration. “Do people have tools? Do they bring their own tools? What makes sense about access to shared resources?”

Marathon Farm’s first three years may not have entirely fulfilled the Department of Public Property’s prerequisite for discussing a longer term lease, that in Dunn’s words, “everything work well and go smoothly.” But with community leaders emerging, neighbors hope that they’ll be given the chance to make the project work.

Sam Gainsburg, a Fairmount resident who gardens a plot at Marathon Farm, hopes to revive the farm under community control. She’s led discussions with Borish and the Greater Brewerytown CDC (GBCDC) and WGCC, and also organized a garden cleanup on November 16 that included the two groups. “My goal is for this committee to make democratic decisions and apply for different grants and programs together.” Gainsburg said. “I really want to hear from the community and find out what they need from the space.”

The people invested in the future of the farm say they will prioritize community ownership and shared responsibility for the space, a pivot from a failed model that depended heavily on a single organization, Marathon. “We need manpower, knocking on doors, cleaning, rebuilding the raised beds,” said Gainsburg, who would also like to help reinvigorate the farm stand and create a new partnership with WGCC.

Striking this balance will only become more vital as Brewerytown continues to slowly gentrify. “We’re working on a structure that’s inclusive of the native population and newcomers to the neighborhood,” said Charles Holliday of GBCDC. “Right now the system we have in place resembles squatting. It’s going to take time. It’s only been two years. I don’t know that the community was ready.” Branch laments that African - American residents living adjacent to the farm have not become more involved, but he agrees it will take time and a consistent presence.

Borish has become involved with the project again in recent weeks, but won’t necessarily have a future role with the farm. “I feel sad about the condition of the farm,” said Borish. “It’s clear that I haven’t done a great job. Have I lost some passion for the project? Yes.” He added: “I’m willing to have any or no involvement. Whatever is in the best interest of the folks taking over the farm.”

Meanwhile, Gainsburg is thinking through the logistics of how to create a shared sense of ownership and collaboration. “Do people have tools? Do they bring their own tools? What makes sense about access to shared resources?”

Marathon Farm’s first three years may not have entirely fulfilled the Department of Public Property’s prerequisite for discussing a longer term lease, that in Dunn’s words, “everything work well and go smoothly.” But with community leaders emerging, neighbors hope that they’ll be given the chance to make the project work.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed